AHO Masters Studio: The Forest

The Forest was a masters studio at AHO during the autumn semester of 2020. The studio explores the forest north of Oslo, Oslomarka/Nordmarka. It takes its basis in the clearings that are formed within the forest, natural or from timber harvesting.

These spaces, as well as the forest as a whole, was investigated for their potential values as a space for the public. The final projects had a main precedent in the old ‘Tings’ that were viking age forms of ‘democratic’ governance. We were looking at how forest clearings might still have a function within the political/government space.

The project did not aim to be about buildings, but rather how the landscape can help drive the narrative, and function not only as a backdrop, but as an ‘active’ member of the space and its function.

An Equal Space for Democracy

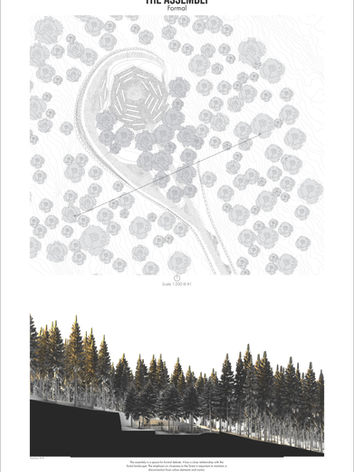

‘An equal space for democracy’ explores a forest clearing, in Oslomarka, as a space of democratic, political, debate. The forest clearing looks into this through formal and informal spaces, and through editing the clearing in regards to its functions. One of the key aspects of the project is the utilisation of trees as both a negative space when they are cut down, in the form of the edited clearing, and as direct interventions within platforms of communication. Letting the trees partake as a member of the space, and create a material palette that is complimentary for the forest.

A core argument for moving, or placing, a democratic debate to the forest is to avoid the spatial prejudice you might experience in the city. Specific spaces have specific values, and expected ways of acting. The argument is that the forest could try to function as an even playing field. The forest should in a sense deconstruct typical formal constructs and act as a social stabilizer that encourages more people to interact and engage with politics.

The concept of ‘Democracy Festivals’ is common in the Nordic and Baltic regions, with events like Almedalsveckan in Sweden and Arendalsuka in Norway (Democracyfestivals, 2019). These festivals recognise democracy as more than just institutions and written rules. They open the stage for both informal and formal conversations. They promote civic engagement, and have a culture where opinions across the board are open for discussion.

The clearing aims to be a space where these discussions can take place. Often when walking past someone in the forest, you end up having a conversation, but when walking past someone in the city this is less likely to happen. By using the forest as a location for a democratic festival, we are hopefully able to generate a disconnect from the city that gives this lower threshold of conversation. This is important in leveling the discussion and generating an equal space.

During research I came across a text from the journal 'Parliamentary Affairs’ that tackled ‘The Power Behind the Scenes’ and the importance of informal spaces’ (Norton, 2019). The text talks about how informal meetings are “...an intrinsic part of parliamentary life…” (Norton, 2019:261).additionally it touches on how corridors, or what I would consider liminal spaces, cause chance encounters that can produce impact on the passing of legislatures. This becomes quite important, as it establishes three types of interactions and spaces; liminal, informal, and formal with these spaces having different forms of communication happening within them. To an extent this text triggered my investigation into formal and informal spaces, and how spaces could become formal or informal.

From there I started to examine the spatial semiotics I perceived in spaces where people gathered for debates and discussions. With the intention of implementing these into the forest and integrating them into the landscape. Their integration into the landscape is important, because it stages a disconnection from urban norms, ergo allowing for a debate without the traditional walls of the city.

Formal spaces are, to me, clear in their intent, and the users have to interpret very little. There is a sense of focus within these spaces, which makes them clear to read. In terms of spaces where people gather for discussion, you normally have clearly defined seating that is focused towards a platform or stage. As this project is trying to generate debate, I found it important to make a distinction between spaces that facilitate monologue vs spaces that create dialogue. With the latter having a spatial arrangement that embraces parity between the audience and speaker; an equivalency that replaces the hierarchy of a monologue.

The informality is, within this project, achieved though non-specificity. The point of the informal gathering space is to create a more spontaneous space within the clearing. This space is made to function during a democracy festival, but also to have a role outside of these events.

Because specific items denote specific use, this space is looking at ambiguous interventions to enhance informal interactions and elasticity in use.

The point of generating ambiguity though form and function is to let loose from innate, established, attitudes of conventional objects/furnishing.

The ambiguity of the space does not mean that they do not have a suggested use. They will specifically have suggested uses, but the form itself should not be instantly clear. There is room for interpretation.

The informal space is layed out through a series of platforms, and these platforms are all oriented towards a central platform.The layout is informed through a zone of hearing from the central platform which is done to allow for spontaneous interaction between the platforms.

When differentiating between formal and informal I put emphasis on how objects operate in space, and how they might be interpreted. The simplified distinction of focus vs ambiguous is based on perceived cohesion and intent within the spaces. However, even within the informal space, there is an intrusion of formality in the design. This comes from the setting out of the platforms, and their general orientation towards a centre, which is formed as a defined circle.

The formal setting-out is done to reinforce the opportunity for spontaneous connections between the platforms to generate larger discussions.

These centres within the formal and informal spaces are connected to a series of sightlines that are defined by paved patches within the clearing. These are there to bind the space together, and to help generate clearity in circulation.

Throughout the design there has been a consideration towards how the maintenance of the clearing will be held. While the surrounding forest should keep its current harvesting categories it should switch to a selection cutting program to maintain forest mass and diversity and the edge defined within the project should be maintained. Trees that are cut down during the maintenance of the edge should be used to expand the gathering spaces, or maintain interventions within the clearing. So as long as a tree does not block a sightpath, damage the clarity of a space or circulation route, it should be allowed to grow until it is fit for use in an intervention.

Having the trees become part of the interventions once they were cut down was key for reinforcing the narrative of the space. This runs parallel to the idea of not bringing in urban materials to the forest. The pine and spruce trees that dominate the clearing, should not lose their presence once cut down. Their use, and narrative propagate through the interventions in the forest. During their lifespan, the trees will grow, reproduce, get cut down, and slowly deteriorate. They bring a constant narrative of change, a change that especially strengthens the idea of informality within the gathering.

The trees too become part of the conversation, this is perhaps most evident in the ‘fallen tree’ seating arrangement.Trees on the edge of the clearing, or specifically planted trees, can be cut down with the trunk of the tree resting on top of the tree stomp. This becomes an area for sitting, gathering. The tree is part of the space through growth, and is cut down once it has achieved the desired length and width to function as part of a platform.

Any seating arrangement within the clearing has a focus on timber, while the ground that makes up a platform is ‘paved’ with natural stone.

As part of the broader scheme, these interventions will deteriorate and change. This means that the pioneer trees that start to grow over time, will eventually make their way into the scheme, maintaining both the clearing edge and the functions of the intervention.

Bibliography

Democracyfestivals. (2020) Intro At:https://democracyfestivals.org/ (Accessed on 3. October 2020)

Norton P. (2019), Power behind the Scenes: The Importance of Informal Space in Legislatures, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 72, Issue 2, April 2019, Pages 245–266, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsy018

Related readings, theory and research from Phase 2 - Not referenced in text

Almedalsveckan. (2020) At: https://almedalsveckan.info/ (Accessed on 3. October 2020)

Anderson, R. (2019), Adolphe Appia: ‘Luminous - Very Luminous’

https://drawingmatter.org/adolphe-appia-luminous-very-luminous/ (Accessed on 20. October)

Arendalsuka (2020) Info At:https://arendalsuka.no/ (accessed on 2. October 2020)

Democracyfestivals. (2020) Folkemodet, the peoples meeting At: https://democracyfestivals.org/folkemdet (accessed 3. October 2020)

Fujimoto, S. (2014) Every kind of architectural definition has an in-between space [online lecture] 8. Jan 2014 At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iJfJSgp8KGQ (Accessed on 3. October 2020)

Fujimoto, S. (2018) Reinventing the relationship between nature and architecture [online lecture] 11. Des 2018 At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=20mKiyvxXjg (Accessed on 3. October 2020)

Luhmann, N. (2012) Theory of Society Volume 1. Translated by Rhodes Barrett.

Stanford: Stanford University Press

Note: As a backdrop to The Autopoiesis of Architecture vol1&2

Luhmann, N. (2013) Theory of Society Volume 2. Translated by Rhodes Barrett

Stanford: Stanford University Press

Note: As a backdrop to The Autopoiesis of Architecture vol1&2

Myers, D. (2015) Exploring Social Psychology Seventh Edition.

McGraw-Hill Education: USA

Note: Particularly the chapters on prejudice

Ranciere, J. (2016) ‘The Aesthetic Today’ Jacques Ranciere in conversation with Mark Foster Gage [online] At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4RP87XN-dI&t=1s (accessed on 27. October 2020)

Schumacher, P. (2011) The Autopoiesis of Architecture: A New Framework for Architecture.

Wiltshire: Wiley

Note: Particularly 5.1 Architecture as Societal Function System - p363-390

Schumacher, P. (2012) The Autopoiesis of Architecture: A New Agenda for Architecture.

Wiltshire: Wiley

Note: Particularly 6.8 The Semiological Dimension of Architectural Articulation - p167-200

Schumacher, P. (2020) Expanding Architecture’s core competency [Online lecture] At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LyaXCwxoqos&t=694s (accessed on 17. November 2020)

SverigeRadio (2020) Karnevalen i Almedalen At: https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2795&artikel=5185228 (accessed on 3. October 2020)

Thomas, J. (2020) Understanding How Liminal Space is Different from Other Places At: https://www.betterhelp.com/advice/general/understanding-how-liminal-space-is-different-from-other-places/ (Accessed on 2. October 2020)

Vittorio Aureli, P. Tattara, M. (2019) Platforms: Architecture and the Use of the Ground

https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/conditions/287876/platforms-architecture-and-the-use-of-the-ground/ (accessed on 19. October 2020)

Zimmerman, P, T. (2008) Liminal Space in Architecture: Threshold and Transition. “Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2008.

Https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/453